This article is more than 1 year old

What made a super high-tech home in Victorian England? Hydroelectric witchery, for starters

Forget the scones and gardens, Cragside house is engineery

Geek's Guide to Britain Imagine an ageing magnate in his private retreat, and you might picture English industrialist William – first Baron – Armstrong in the luxurious wood-panelled library of his Northumberland pile: Cragside.

Sitting at his desk, Armstrong gazes out at acres of private forest. An onyx-and-marble-surround fireplace to his right, in-house spa with Turkish bath and plunge pool downstairs.

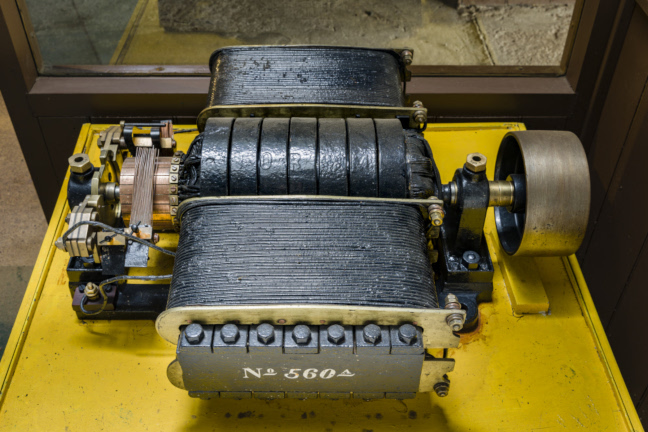

But Armstrong wants something more: power – and he knows how to get it. He orders the butler to telephone an underling ("the Caretaker of the Electric Light") in a small, nearby building which houses a hydraulic pump fed by water he had dammed up from some nearby lakes as well as a 6-horsepower turbine driving a Siemens dynamo – rare for its age, even rarer in this setting – that would generate electricity. That electricity proceeds to power the first installation of the lightbulbs developed by his friend in Cragside, the world's first hydroelectric-powered house.

Welcome to the first house powered by hydroelectricity and it's thanks to Armstrong – a classic Victorian high-achiever: visionary industrialist, controversial arms dealer (it was acceptable in the 1880s – Ed) and pioneering inventor.

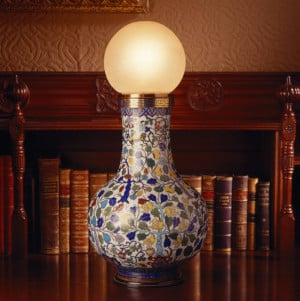

Seat of power in Armstrong's Library. Photo ©: National Trust Images/Andreas von Einsiedel

Even by the standards of the age, Armstrong was a character of immense energy – something he channelled into making his sprawling, rural Northumberland retirement pile and its grounds a test bed for new ways to generate and use electricity.

During the course of his time at Cragside, when he extended the property, Armstrong installed heating and power devices in the kitchens in addition to electrical lighting.

Cragside was a showcase property, attracting the interest of royalty, German industrialists and famous American and British inventors.

But Armstrong was no nerd, toiling for the sake of creation: his inventions were intended to simply make Cragside work better and perhaps because of this Cragside is not devoted to its technology heritage. While the National Trust, which has owned the house since 1977, proclaims Cragside as "the home of hydroelectricity", many visitors are here to see a rich Victorian's house with its grand rooms, servants' quarters and spacious grounds.

But if you want to uncover its tech legacy, it helps to know what to look for. Fortunately, we're here to help.

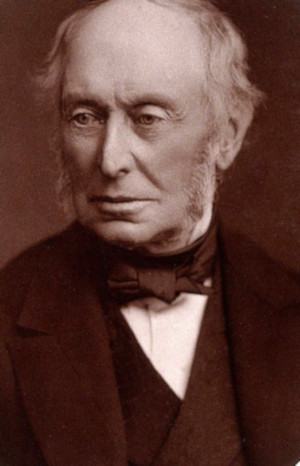

The official tour of the house starts in the servants' quarters but our power tour starts with the man.

Handle with care – one of Armstrong's enamel-base lights. Photo © National Trust Images/Andreas von Einsiedel

Born in 1810 in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and the son of a corn merchant, Armstrong seemed destined for a career in law but displayed an early interest in hydraulic engineering. It's said his family joked he had "water on the brain" but Armstrong proved his interest was no laughing matter.

Armstrong first made his name with the creation of the hydraulic accumulator tower – a taller example of which you'll find at the entrance to Grimsby Dock. This energy-storing tower was used to multiply the force of water pressure that was necessary to power the waterside's hydraulic equipment.

Armstrong successfully completed a series of experiments involving hydraulic cranes for use along the dockside in Newcastle and then – through his company, WG Armstrong – installed hydraulic tech in gates and bridges across the nation, including one very high-profile landmark in the nation's capital.

Tower Bridge opened in 1894, and the Armstrong company provided the hydraulic lifting gear that operated the bascules, the "drawbridges" that are lifted to allow taller boats underneath. The equipment was designed and installed by Hamilton Rendel, who spent his career working for Armstrong's company, and Henry Brunel, the son of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who similarly worked for the company for many years. It was taken out of service in the 1970s, but can still be seen in Tower Bridge's museum.

From water to weapons and back – William Armstrong

From water to weapons

But – as seems to be the Victorian way – Armstrong couldn't limit himself to just a single pursuit and the company segued into weapons. Armstrong in 1855 produced a successful breech-loading artillery piece that was lighter and more accurate than the equivalent weaponry of the time. This lead to a knighthood and a monopoly for his factory in Elswick on Tyneside to supply the British government – to which he surrendered the patent. The contract was cancelled following criticism of the guns' performance.

Armstrong, however, did rather even-handedly supply arms to both sides in the American Civil War.

Enter Cragside. The house came into Armstrong's life in 1863, when the inventor-industrialist bought the land in the wake of a fishing trip. It would be here that Armstrong spent more time following a bruising defeat in a strike by his engineering workers, who had demanded to work a mere nine hours a day.

He spent time buying paintings and added new rooms, but Armstrong also wanted to install the latest technologies and turn Cragside into a comfortable retirement nest.

If anything, Cragside is best known for electric lighting and 1878 saw the opening of this particular chapter with the installation of an arc lamp in the art gallery, courtesy of Armstrong's pal William Siemens – one of the founders of the German technology group who was, like Armstrong, a former president of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Arc lamps send electricity through an arc between carbon electrodes, generating carbon monoxide, heat and sometimes sparks. Andrew Sawyer, Cragside's conservation manager, told us: "It's a very dirty and smelly way of lighting, but there was no alternative at that stage.

"He was keen to see if he could light pictures with it – which would be very frowned upon from a conservation point of view these days."

Next up was the incandescent lightbulb. Experiments with electrically generated light dated back to the 1830s, but Joseph Swan – another of Armstrong's friends – had demonstrated a usable bulb in December 1878. In the US, Thomas Edison built on Swan's work and showed his equivalent a year later.

Armstrong's labour-saving dishwasher. Photo © SA Mathieson

Swan and Edison became locked in a dispute over who exactly had invented the incandescent lightbulb. A court eventually ruled they had both invented it – just independently, a decision that led to Swan and Edison merging their UK companies under the name Ediswan.

Ahead of that, however, Armstrong offered to install Swan's kit at Cragside partly to support him as the true inventor of the incandescent lightbulb.

These eight lights in Cragside's library, fitted in 1880, are reckoned to be "the first proper installation" of the invention. There were, however, quite a few wrinkles to be ironed out – such as how to turn them off. Four of the bulbs rested on exquisite vases, previously used as gas lamps – which did more than just support them.

"These vases, being enamel on copper, are themselves conductors, and serve for carrying the return current from the incandescent carbon," wrote Armstrong in a letter to The Engineer in January 1881, adding that a wire led down from the bulb to a cup of mercury.

Siemens Dynamo, inside the power house. Photo © National Trust Images/Andrew Butler

"Thus the lamp may be extinguished and relighted at pleasure merely by removing the vase from its seat or setting it down again," he added.

This was a time before health and safety laws.

"Nobody quite knows how it worked," said Sawyer, given that turning the lamp off would mean lifting an electrified vase. Fortunately, switches were invented shortly after. Armstrong expanded his lighting across the house and by the time of his letter to The Engineer in January 1881 he had already installed several dozen.

Smart home

This setup was powered by what was possibly the world's first hydroelectric power station. Armstrong had been thinking about alternative sources of energy for some years, having helped investigate the performance of local coal in 1855 in response to the Royal Navy switching to Welsh coal. Armstrong in 1863 predicted England would stop producing coal within the next 200 years – 152 years later deep coal mining did indeed come to end with the closure of Kellingley Colliery in North Yorkshire in December 2015 – although some surface mining continues. This industrious industrialist saw a great future for electricity produced using water, and was interested in the potential for solar, wind, tidal and chemical energy.

Cragside was partly developed as a place to show off to visitors. On 19 August 1884, the Armstrongs hosted the prince and princess of Wales and their five children, using electric light to great effect. "From every window the bright rays of electric lamps shone with purest radiance," gasped the Newcastle Daily Journal.

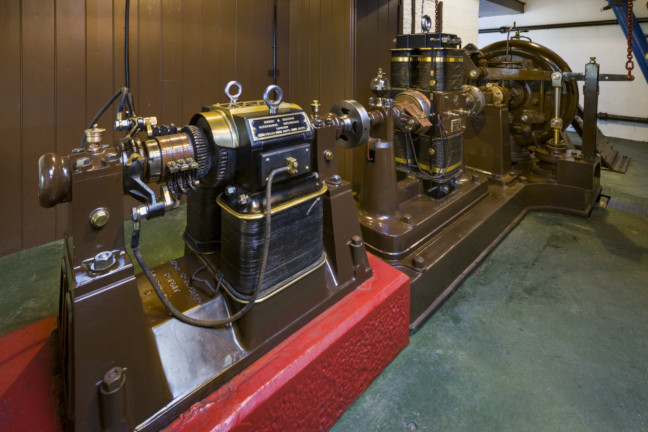

Inside the power house. Photo © National Trust Images/Andrew Butler

But more importantly, Cragside was Armstrong's great retirement project. He was heavily involved in designing changes to the house and estate, with an on-site laboratory and dedicated staff for electrical work.

He was connected to leading scientists and engineers, in many cases buying their inventions for installation in the house or grounds. "He was known for going into a trance-like state with his hand on his head and the other in his pocket and was oblivious to what was going on around him," Sawyer said, with the result that people wondered if he was still breathing. "For me his greatest gift was the ability to gather amazing people around to achieve his dreams."

Taking the tour of Cragside provides the opportunity to see the results of Armstrong's technological dreams and attempts to make life more comfortable. One of the best places to do so is in the servants' basement quarters.

The kitchen includes a wall-mounted rinsing dishwasher and a meat turner, both of which used water pressure rather than electricity. Next door is the jigger room, which used to drive the house's hydraulic lift, installed in the 1870s and drawing on Armstrong's experience of hydraulic cranes. The lift has since been replaced, but this room explains how it worked. Elsewhere in the basement above the door of the butler's pantry is a display unit for the system of electric servants' bells.

The ground floor's highlight is the library, a gorgeous room where you can take a close look at the four pioneering vase-lights, illuminating paintings of the Armstrongs. Don't expect signs pointing them out, but there are information sheets and usually volunteers for those interested in knowing more about the technological significance of this room.

Cragside's waterwheel. Photo © SA Mathieson

The staircase to the first floor features more early electric lights borne by wooden beasts. Those focusing on technology could skip the apparently endless parade of fancy bedrooms upstairs, but at the far ends of the first and second floors are two electric-powered gongs, installed by Armstrong to let guests know it was time to dress for dinner.

After going through the art gallery (which is no longer lit by smelly arc lamps), visitors enter a giant drawing room with a bonkers, 10-tonne Italian marble chimneypiece. It is doubly pointless: the room is partly built into the hillside, so smoke had to be diverted into a separate chimney away from the ornamental one. More fundamentally, following his belief that burning coal on open fires was inefficient, Armstrong was closely involved in designing an underfloor central heating system in Cragside's first expansion in 1870. This uses an enclosed boiler and a network of pipes, while the open fireplaces only ever burnt wood and peat. "Really, it was the first eco-home," Sawyer said.

Around the corner and through a billiard room is the small electrical room once used by Armstrong as his lab. This is the place where Cragside's technological legacy is most obviously celebrated, with video versions of some of his experiments. Unfortunately, it can get cramped when busy, making these hard to see.

The Archimedes screw. Photo © SA Mathieson

Cragside's electrical and hydraulic devices depended on power from the house's grounds. Its name is appropriate, as much of the estate is taken up by steep forested hillsides. It is a great place to explore for the scenery, but a few locations reveal more of its technological legacy, with all of the following marked on the free map of the grounds offered on entry.

The original 1878 power house, which used 1,370 metres of copper wire to connect to the main house, was made obsolete by Armstrong's increasing lust for electrical power. In 1886, he built the Debdon Burnfoot power house, which is part of the present-day estate. It is a modest building, about half a mile's walk from the garden's graceful iron bridge, surrounded by woodland with a waterwheel nearby. Inside, there are panels explaining how things work, as well as the power generation kit which can be activated by a button.

Near Tumbleton Lake, which most visitors will drive past on the way into the car parks, is a 17-metre Archimedes screw installed in 2014. It sits on one of the dams ordered by Armstrong to create the lake to generate power from the difference in water height between it and Debdon Burn. When working, the screw powers the LED lights in the house's showrooms, with the National Grid connection that was installed by the Army when it occupied Cragside during WWII as a backup. On arriving, an officer found that the original electrical system could only cope with nine lights on at once.

"It used to be our proudest boast that this is the first house in the world to be lit by hydroelectricity," said Andrew Sawyer. "And now we can end that sentence with 'we still are'."

While these parts of the grounds are best explored on foot, the wider estate can be experienced by taking the 9.7km (six-mile) carriage drive, a one-way road with a restful 15mph speed limit and numerous car parks. About halfway round and high up on the hillside are the two Nelly's Moss lakes. These were originally bogs that Armstrong had converted into lakes to provide more pressure for power generation. Frogs, toads and herons can be seen and there is an easy and fairly level 2.4km (1.5-mile) walk around them, starting from the Crozier car park.

Armstrong's hydraulic reach was felt across the country. Photo © City of London, London Metropolitan Archives

Having soaked that in, you can soak up some refreshments at the small café next to the main house or a much bigger visitor centre on the other side of the long car parks built into the hillside. There are activities for children, including an adventure play area and a labyrinth.

Beyond Cragside, wild and rural Northumberland has lots to offer visitors, although you can expect to spend a lot of time travelling. Alnwick has an amazing castle that's featured in the Harry Potter films and offers themed engagements for children. Also, there's the Duchess of Northumberland's spectacular 21st-century gardens, featuring a 120-jet grand cascade and a fenced-off poison garden with belladonna, hemlock, tobacco and cannabis.

Further north on the coast is Bamburgh Castle, which overlooks a wild sweeping beech. To the south lies erstwhile Roman Empire frontier Hadrian's Wall, with forts including Chesters and Housesteads and the amazing collection of items found at the archaeological site of Vindolanda.

To the unstrained eye or casual observer, Cragside may seem to be just another of Britain's posh country houses – albeit newer than most. But by installing lights powered by hydroelectricity and other inventions, Armstrong pioneered an idea of living that became global – even if, sadly, electric dinner gongs never really caught on. ®

GPS

55.3137, -1.8857

Postcode

NE65 7PX

Getting there

By Car: From the south, take the A1 to Morpeth, A697 to Coldstream, B6344 west to Rothbury, then on reaching the town take the B6344 north-east and look for the entrance sign. From the north, leave the A1 at Alnwick and take the B6341 west, crossing the A697. Satnav may propose using the estate's one-way exit road rather than its entrance, so follow the signs.

Train and bus: Nearest mainline station is Newcastle Central with Morpeth served by local services. Arriva X14 bus starts at Newcastle Haymarket bus station, goes via Morpeth and stops on the edge of the estate. To reach the house, get off in Rothbury and walk up the B6341 to the main entrance.

Entry

Prices: 16 February to 3 November 2019, £20.90 adult gift aid/£19 standard, child £10.50/£9.50 family £52.30/£47.50. Free for National Trust members. Parking free.

Opening hours: From 16 February 2019, the house opens daily from 11am to 5pm. November to mid-February, the house is partly closed – check the website for details. The grounds open every day except Christmas Eve and Christmas Day from 10am to 3pm in winter, then from 10am to 5pm after mid-February.