This article is more than 1 year old

Boffins, Tunnel Tigers and Scotland's world-first power mountain

The hollowing heroes who reversed nature

Geek's Guide to Britain In the middle of a Scottish mountain is a man-made cavern 90 metres high and 36 metres long - tall enough to stuff an entire Cathedral in its belly - which is only accessible through a kilometre-long rock tunnel. This is the home of the Cruachan Power Station.

In 1921 - with one world war down and one to go - the British government surveyed its mountains with a view to generating hydro-electric power. That survey established that Cruachan, near Oban on the west coast of Scotland, would make an ideal site for storing power - if only the technology existed to make it practical.

One world war later, the technology had arrived. Within a decade, nuclear power was generating an overnight excess in need of storage, so in 1959 they broke ground to build the world's first reversible-turbine power station, which essentially uses large amounts of water to store excess energy.

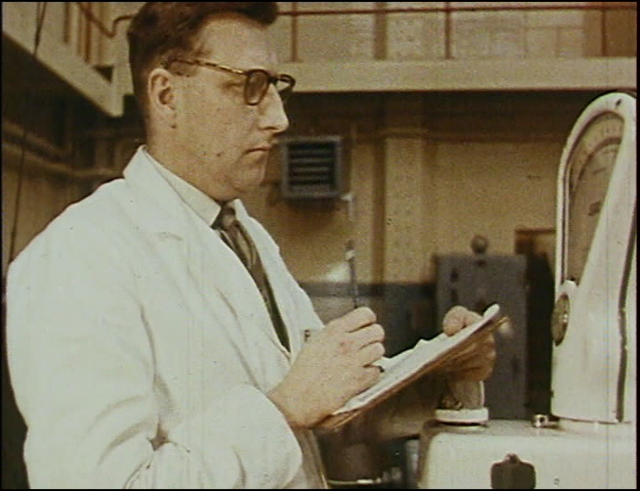

Only boffins of this calibre could realise the dream.

Still from Cruachan, The Hollow Mountain, National Library of Scotland.

That power station now comprises an artificial loch, dammed with 200,000 tonnes of concrete and storing 7 gigawatt-hours' worth of water - 22 hours supply with a 12-hour reserve. That water drops down a sloping 305 metres into four turbines housed in the middle of the mountain, where we're allowed to visit them.

The idea is simple to explain, rather harder to realise: water falls from the loch above through turbines to generate electricity, 440MW of it at peak, but at night the same turbines are turned (using excess power) to push the water back to the top loch again, making the whole thing a huge storage battery designed to buffer between the constant generation and variable consumption of electricity.

The outwards sign of something significant within

Not that you'd know it driving past Cruachan. The only signs that give away what lies beneath are the suspicious number of pylons - and a large sign pointing visitors towards the centre. Once you've got there, you can buy tea and cake, buy postcards and novelties, press buttons in the exhibition and board the minibus which takes visitors to the heart of the mountain.

Descending into the bowels of the earth, The Channel Tunnel should look like this

Cruachan's biggest problem in becoming a hydro plant was the lack of upper loch from which water could flow. The mountains had a nice valley but it drained neatly into Loch Awe, so the first order of business was to build an enormous dam. That took two years, thanks to the remote location and inclement weather, and below the dam shafts were dug at a 55° incline to ensure a smooth flow of water to the four generators below in their huge machine room. It is that scale of construction which most impresses.

Three contractors took on the project: one for the aqueducts, one for the tunnelling and one for the fitting out. Each brought in gangs of workers from around the UK, totally 1,300 men at its peak, accommodated in temporary camps which promptly became rife with drinking and gambling as the self-styled "Tunnel Tigers" relaxed in the way unique to young men whose employment involves considerable risk to limb and life.

Real men packing real explosives into the wall.

Still from Cruachan, The Hollow Mountain, National Library of Scotland

Thirty-six men died in all, 15 underground digging out the cavern and the rest in the construction of the tunnels and network of aqueducts feeding the upper loch.

There are four-and-a-half kilometres of aqueduct and more than 14km of tunnels catching rainwater from the surrounding hills. That rainwater took nine months to fill the reservoir and still contributes about 10 per cent of the power generated.

Having driven the kilometre into the mountain, visitors leave the bus and climb a short flight of steps to a sloping path past the fire system - where 20,000 gallons of water sit just in case they're ever needed. Our guide, the slightly over-enthused Ian, tells us that the system is tested twice a week, but has never been used.

From there we're led past tropical plants, carefully placed to emphasise the heat - that far underground it remains a steady 18°C - and some of the tools used to dig out the caverns.