This article is more than 1 year old

Malware crooks find an in with fake browser updates, in case real ones weren't bad enough

Researchers say ransomware could be on the horizon if success continues

An uptick in cybercriminals masking malicious downloads as fake browser updates is being spotted by security researchers.

Mimicking the success of the tactics adopted by the years-old SocGholish malware, researchers at Proofpoint have drawn attention to cybercriminals increasingly emulating the fake browser update lure.

Researchers have tracked SocGholish for more than five years. In the past five months, three more major campaigns have emerged. All use similar lures but deliver unique payloads.

The fear is that despite only dropping malware now, the proliferation of these campaigns could be a boon to initial access brokers, offering an effective route to infect end users with ransomware.

SocGholish is the oldest major campaign that uses browser update lures. It is typically attributed to TA569. In August, it was revealed to have facilitated the delivery of malware in more than a quarter (27 percent) of incidents. It was among the top three malware loaders that altogether accounted for 80 percent of malware attacks.

It was also responsible for pushing malware to hundreds of US news websites last year after the attackers were able to manipulate a JavaScript codebase that was served to the sites.

The RogueRaticate campaign, otherwise known as FakeSG, was spotted by Proofpoint in May 2023 but its activity may date back to November 2022.

It's the first major fake-browser-update campaign to emerge since SocGholish and typically leads to the NetSupport RAT being installed on the victim's machine.

A month later in June, the first activity from the ZPHP campaign, also known as SmartApeSG, was spotted and finally made public in August by Trellix.

Like RogueRaticate, ZPHP also most often leads to the installation of NetSupport RAT, which has been infecting machines since around 2017, according to SentinelOne.

The most recent of the four campaigns is ClearFake, which was first spotted in July and made public in August by researcher Randy McEoin.

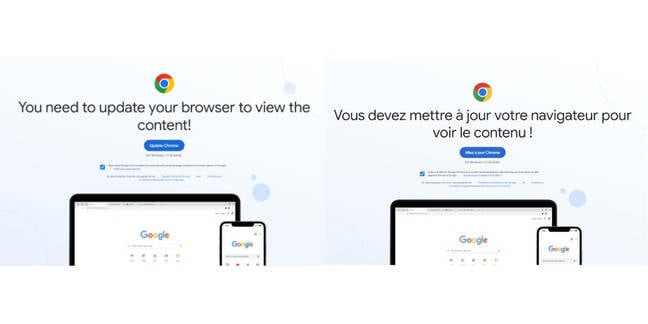

Proofpoint characterized ClearFake as a campaign that drops infostealer malware and is able to tailor lures not just by the user's browser, but by their language too, widening its pool of targets.

How the attack is carried out

Each campaign differs slightly in the way in which it delivers the lure and malware payload at the end, but they tend to follow a three-stage structure and all tailor their lures based on the user's machine and browser.

The first stage sees a legitimate but compromised website injected with malicious code. Stage two refers to the lure and the traffic that goes between the attacker-controlled site and the user, which is filtered to prevent discovery. Stage three refers to the end payload being delivered.

SocGholish's operators, TA569, use three different means of transitioning from stage one to stage two of the attack. Two of these involve using different traffic distribution systems (TDS) and the other uses a JavaScript asynchronous script request to direct traffic to the lure's domain.

RogueRaticate and ClearFake use TDS only when the second stage is reached, underlining the differences between the campaigns.

- US cybercops urge admins to patch amid ongoing Confluence chaos

- We're not in e-Kansas anymore: State courts reel from 'unauthorized incursion'

- BLOODALCHEMY provides backdoor to southeast Asian nations' secrets

- Regulator, insurers and customers all coming for Progress after MOVEit breach

Why the attack is successful

Proofpoint said the attack earns success because it understands the cybersecurity training most people receive, and uses that to craft a campaign that leans on end users' inherent trust of legitimate domains and brands.

"In security awareness training, users are told to only accept updates or click on links from known and trusted sites, or individuals, and to verify sites are legitimate," it said in a blog post.

"The fake browser updates abuse this training because they compromise trusted sites and use JavaScript requests to quietly make checks in the background and overwrite the existing website with a browser update lure. To an end user, it still appears to be the same website they were intending to visit and is now asking them to update their browser."

Despite using a social engineering element, researchers noted that phishing isn't often used in any of the four campaigns – attackers aren't sending direct emails with links to the compromised sites, they're being shared by people over email during the course of their normal online activity.

For organizations, it means the threat isn't just an email-based one, and users could feasibly find themselves on a compromised site by clicking a link returned by a search engine, for example.

Proofpoint's advice is to rely on a multi-layered security strategy, including network detection and endpoint protection tools, as well as a robust security awareness program that educates users on the threat.

Monitoring the indicators of compromise (IOC) is often a useful tactic for keeping malware attacks at bay but due to the frequency with which the campaigns change their infrastructure and details in their payloads, it can be difficult to rely on these. ®